Tracking Firmware Code Size

arm-none-eabi-ld: firmware.elf section `.text' will not fit in region `ROM'

arm-none-eabi-ld:: region `ROM' overflowed by 16 bytes

make: error: arm-none-eabi-ld returned 1 exit status

make: *** [firmware.elf] Error 1

This is the terminal output of my nightmares. It frequently means a halt in productivity and sends engineers scrambling to save 100 bytes wherever they can, all while trying to meet the deadlines and requirements set forth by the Product team.

Fortunately, this message doesn’t always have to come as a surprise. Where I’ve worked in the past, we had the tools and infrastructure in place to know when we would run out of code space, as well as where it all went. These tools were immensely helpful when our team at Pebble was trying to cram an 653kB firmware into a 448kB ROM region.

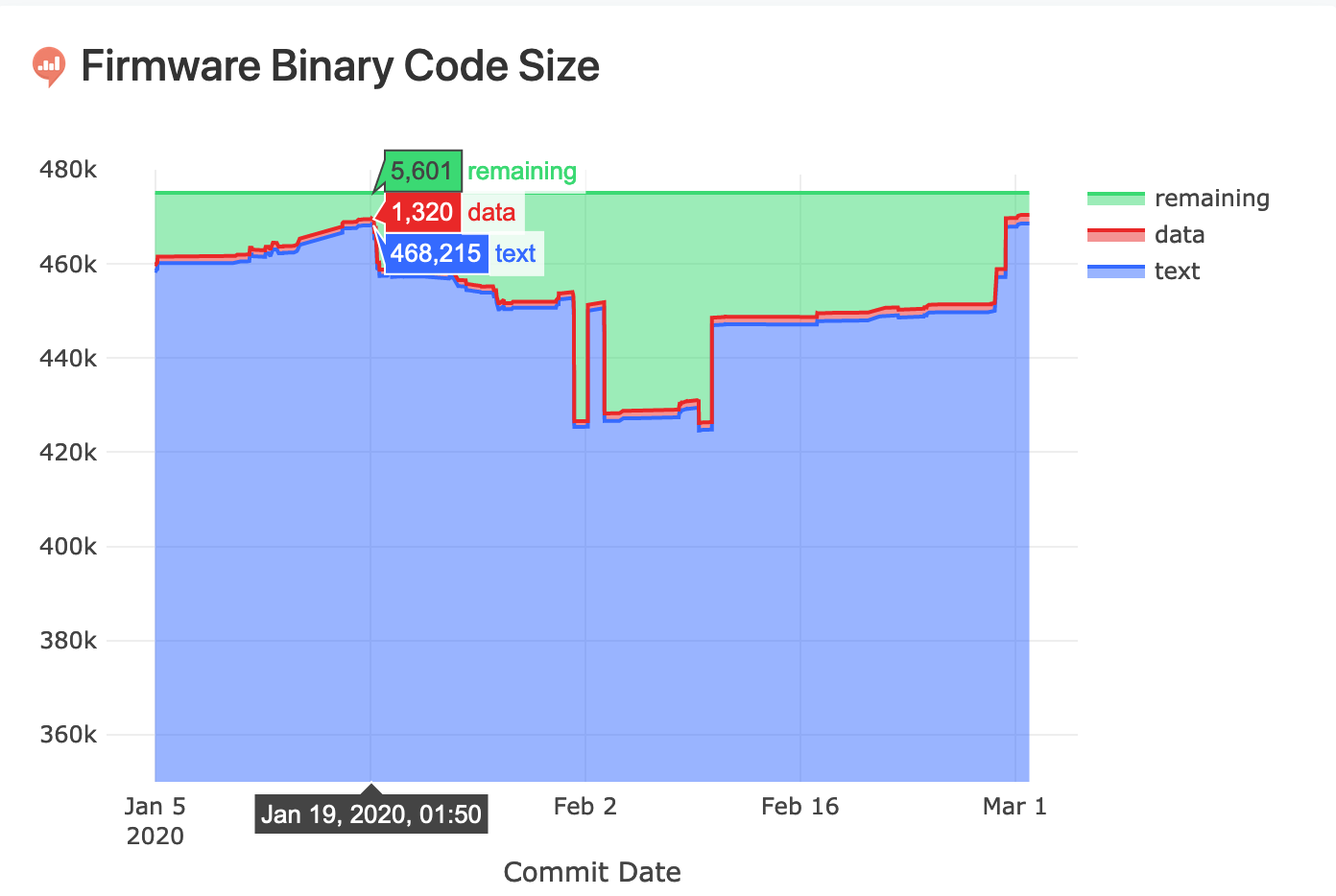

Below is an example of a type of dashboard we had. When we approached 5kB remaining in our firmware image, we knew what to do.

In this post, I will show you how to set up a code size dashboard for your project. I’ll cover why should track code size, how to do it, and the steps to calculate code size deltas on every pull requests to keep it to a minimum.

If you want to skip ahead to see what we’ll be building in the post, check out this example code size dashboard for the Zephyr Project.

Table of Contents

Why Track Code Size?

If you are a firmware engineer, you’ve likely run into code sizes issues. Firmware, like a gas, will expand to take up all available space, whether it’s extra debug logs, a full featured command line interface, or fancy animation & images.

With this in mind, it is wise to constantly track and measure the code size of a project during development to know when and why the code size grows. This means that each commit and a handful of build configurations should be tracked so an accurate picture can be painted.

Most projects simply print out size information after each build. It may look like this:

Memory region Used Size Region Size %age Used

FLASH: 153108 B 1 MB 14.60%

SRAM: 44544 B 256 KB 16.99%

IDT_LIST: 56 B 2 KB 2.73%

This is a step in the right direction, but it does not give us any sense of the changes to code size over time. Instead, we must track this information from commit to commit. With this information, your team can:

- Prevent large (possibly accidental) code size increases due to non-optimal

code for function usage (e.g. a few years ago, by adding a call to newlib’s

sscanf(...), I increased the firmware size by 2kB). - Retroactively find large spikes or decreases in code size when looking for easy-win optimizations.

- Estimate when the code size will exceed the limit by looking at historical data.

- Over time, learn which coding patterns contribute to the code size increases.

- Calculate code size deltas on every new pull request. You would likely prefer to merge a shiny new feature which adds 2kB of code instead of a poorly implemented bug-fix which also adds 2kB.

How to Track Code Size

In the remainder of this blog post, we will set up a code size tracking dashboard for the popular open-source RTOS, Zephyr1. We also want to take this data and be able to compute the code size deltas between commits to know exactly which commits and by how much each one contributed to the code size.

Since the Zephyr project is massive in the number of examples, boards, and

features that it encompasses, we will restrict the code size calculations to the

examples/net/lwm2m_client example with the cc3220sf_launchxl board. This

example was chosen due to its large number of files and dependencies with a hope

that its code size would fluctuate more than a hello world example with limited

dependencies.

We won’t be covering how to initially set up building the Zephyr project, as there are detailed instructions2 about how to get started. I can’t help but feel the setup would have been simpler and quicker if they had taken advantage of Conda. It would also have the benefit of being cross-platform and version controlled within the codebase.

If anyone working on Zephyr is reading this, you should check out how Conda can make the setup easier 😉.

Goals

By the end of the post, we will be able to:

- Store data about each commit and build with a database.

- Look at historical code size data using visualizations.

- Calculate deltas between a commit’s code size and its parent’s.

- Estimate code size deltas between the master branch and a pull request build automatically.

Let’s begin!

Building the Firmware

After getting the Zephyr project building with the hello world example, this is the following command to build the example firmware.

$ cd zephyrproject/zephyr

$ west build -b cc3220sf_launchxl samples/net/lwm2m_client --pristine

...

Memory region Used Size Region Size %age Used

FLASH: 149936 B 1 MB 14.30%

SRAM: 44544 B 256 KB 16.99%

IDT_LIST: 56 B 2 KB 2.73%

[...]

[188/188] Linking C executable zephyr/zephyr.elf

Zephyr already has some code size statistics at the end of their build, which is great! However, there is room for improvement.

To help generate data for me to work with, I spun up an AWS Spot EC2 instance and built the most recent 2,500 commits of Zephyr from the master branch as of March 14th. I would have built more but there was an issue with the CMake build system and dependencies unfortunately.

The process for this was quite simple. Using git rev-list --first-parent, we

can get all the revisions that were committed into the master branch

chronological order.

$ git rev-list --first-parent master

22b9167acb52386c13be6d22223fd3d585d57a3d

7cb8f5c61e6081475223586349b88c5a34eb7f38

[...]

Once we have all the commits, we can run a Python script that builds every commit.

for commit in commits:

try:

os.system("git checkout {}".format(commit))

os.system("west update")

os.system("west build -b cc3220sf_launchxl samples/net/lwm2m_client --pristine")

# Here, we calculate and update the code size.

except:

continue

To whomever it concerns: I love the

--pristineoption in thewesttool.

Capturing the Sizes

To get a generic code size calculation, we can use size, or in the case of

this blog post, arm-none-eabi-size. This captures the text, data, and

bss region code sizes and prints them to the terminal.

$ arm-none-eabi-size zephyr/zephyr.elf

text data bss dec hex filename

130780 3356 21167 155303 25ea7 build/zephyr/zephyr.elf

There are a number of ways to capture this data, and some projects or teams want to track other data important to them. These might include specific linker region sizes, resource pack size (fonts, images, etc), or possibly the largest 10 files or symbols in the codebase. Whatever is important to you and your team, track it!

Organizing the Sizes

Our goal is to keep track of the sizes of the text, data, and bss

regions for every commit and every build. By storing the commit

revision and the build type, we can perform code size deltas between any

revisions built with the same configuration.

To ensure that we can calculate the deltas between commits properly, we also

need to keep track of the “parent” commit, since the commit that comes before it

in the git log is not necessarily the parent.

A commit’s parent can be found using the following git command:

$ git rev-parse a2bc514653^1

c1fdf98ba5eb393a7646775921630bf4323ed832

To summarize, for every commit, we will store the following information for each commit and build combination:

-

revision:a2bc51465395057e3830614b20ceea10976204bb -

parent_revision:c1fdf98ba5eb393a7646775921630bf4323ed832 -

build:lwm2m_client -

text: 130,780 B -

data: 3,356 B -

bss: 21,167 B

One thing to also be aware of is that if we want our code size deltas between commits and pull request builds to always work, we need to ensure that every single commit in the master branch that a developer could branch from has its code size calculated and stored.

For better or worse, the Zehpyr Project has chosen the “Rebase and Merge”

strategy. This means that a pull-request can have many commits that don’t

successfully build in CI. It also means that to successfully store code size

about every commit, we’ll need to build

count of pull requests * count of commits in each pull request times in our CI

system.

I’ve come around to Phabricator’s “One Idea is One Commit” philosophy, especially in large projects. It greatly simplifies release management and reverts. If this strategy is too heavy of a hammer, I suggest using merge commits.

Determining the Storage

In my opinion, storing the code size data somewhere useful is the most difficult problem to solve. This is because firmware teams are comprised of firmware engineers with a firmware background and limited web or devops experience. It is also a difficult problem because we’ll be calculating and storing code sizes in a continuous integration system and the system needs to be reliable.

I investigated some options and have listed my opinions and conclusions below.

- Persist data within a CI system (CircleCI, Jenkins, etc).

- Storing metadata alongside builds isn’t supported in most CI systems. It’s also unreasonable to keep build metadata for every build around forever.

- Append code sizes into a Google Sheet or Airtable spreadsheet.

- It’s clever, but I imagine getting a Google “App” and authentication approved for use within a company organization would prove to be difficult. Airtable is nice, but their pricing becomes quite high after storing large amounts of data.

- Keep the data in the git repo using

git notes3 4.- I created a prototype of this. It worked, but the complexity increased when storing metadata about more than one “build”. Also, parallel CI machines could cause note merge-conflicts by pushing the notes.

- The beautiful thing with

git notesis that you can see the code size information when runninggit log, which was a nice bonus.

- Push the code size data into a proper database, such as PostgreSQL.

- This is the approach I ultimately took. Databases are great about data integrity and being able to logically group the code sizes by “builds”. They are also fast.

Regardless of what approach is taken, you likely want the ability to quickly list or export all the historical code sizes, query for a single build (for pull-request deltas), and be able to ensure that no duplicates exist.

If you go with the hosted database approach, which I do suggest, either ask the devops/software team for an isolated database or check out ElephantSQL or Heroku Postgres. They both have a free database tier and their pricing is reasonable.

Storing the Sizes

We now want to store our sizes in our newly minted PostgreSQL database. Your database provider or devops engineer will likely give you a URL string that looks like:

postgres://<username>:<password>@<server>:<port>/<database_name>

We can use this in a Python script to insert and fetch rows from the database

using the psycopg2 library. Unfortunately, going into the details, nuances,

and pitfalls about how one interacts with and manages a database is out of the

scope of this post. I have listed SQL operations below that a developer could

use, and I have also written up a

working example

that you can use with a few modifications.

For now, let’s quickly go through using pyscopg2 in a Python script.

First, we need to make a connection to the PostgreSQL database from within our Python script.

DATABASE_URL = os.environ.get("DATABASE_URL", 'postgresql://localhost:5432/codesizes')

url = urlparse(DATABASE_URL)

dbname = url.path[1:]

user = url.username

password = url.password

host = url.hostname

port = url.port

conn = psycopg2.connect(dbname=dbname, user=user, password=password, host=host, port=port)

To initialize the database with our table and all the necessary columns, we

first have to issue a CREATE TABLE command.

cursor = conn.cursor()

cursor.execute("""

CREATE TABLE "codesizes" (

"created_at" timestamp NOT NULL DEFAULT NOW(),

"revision" varchar NOT NULL,

"build" varchar NOT NULL,

"parent_revision" varchar NOT NULL,

"text" int4 NOT NULL,

"data" int4 NOT NULL,

"bss" int4 NOT NULL,

"message" varchar NOT NULL DEFAULT ''::character varying,

PRIMARY KEY ("revision","build")

)

"""

)

conn.commit()

Now we have a database and table that is ready to accept code sizes!

To push one, we’ll use the INSERT INTO operation.

codesize = CodesizeData(

# class with all code size info

)

cursor.execute("""

INSERT INTO codesizes

(revision, build, parent_revision, text, data, bss, message)

VALUES ('{}', '{}', '{}', {}, {}, {}, '{}')

""".format(codesize.revision, codesize.build,

codesize.parent_revision,

codesize.text, codesize.data,

codesize.bss, codesize.message

)

)

conn.commit()

Finally, to fetch a value from the database, a SELECT operation can be used.

cursor.execute("""

SELECT

revision, build, parent_revision,

text, data, bss, message

FROM codesizes

WHERE build = '{}'

AND revision = '{}'

""".format(build, revision)

)

record = cursor.fetchone()

revision, build, parent_revision, text, data, bss, message = record

return CodesizeData(

# Fill in class data

)

All of these code snippets shown above can be found in the Interrupt repo in a mostly working example.

Wrapping these SQL operations with Python and Click makes the operation of “stamping” and uploading a code size something like the following:

@cli.command()

@click.argument("binary")

@click.option("--build", default="default")

@click.option("--revision", default="HEAD")

def stamp(binary, build, revision):

"""

Calculates the size of the BINARY (.elf) provided and

stamps the current git revision with the code size for

the given BUILD.

"""

text, data, bss = _calculate_codesize(binary)

# git rev-parse <revision>^1

parent_revision = _get_parent_revision(revision)

# git log -1 --pretty=%s <revision>

message = _get_git_log_line(revision)

# Insert code size into database

codesize = CodesizeData([...])

_upload_codesize(codesize)

If you are using the examples from above, you’d place something like the following in your CI system after the firmware has been built.

export DATABASE_URL = # set this in a global CI config

$ python ~/codesizes.py stamp build/zephyr/zephyr.elf \

--build lwm2m_client

Visualizing the Data

At this point, we can assume we are storing our code sizes in a database of sorts, and we can now visualize the data. There are many ways to do this, but the ones that come to mind are:

- Export to

.csvand import to Excel. - Build a web application using your framework of choice to show the data in whatever way you please.

- Spin up a Business Intelligence style tool, such as Redash or Metabase.

In this post, I chose to launch a Redash instance on Heroku (takes 5 minutes, it’s ~free) and hooked it up to the PostgreSQL database. This allowed me to create some pretty quick and useful visualizations!

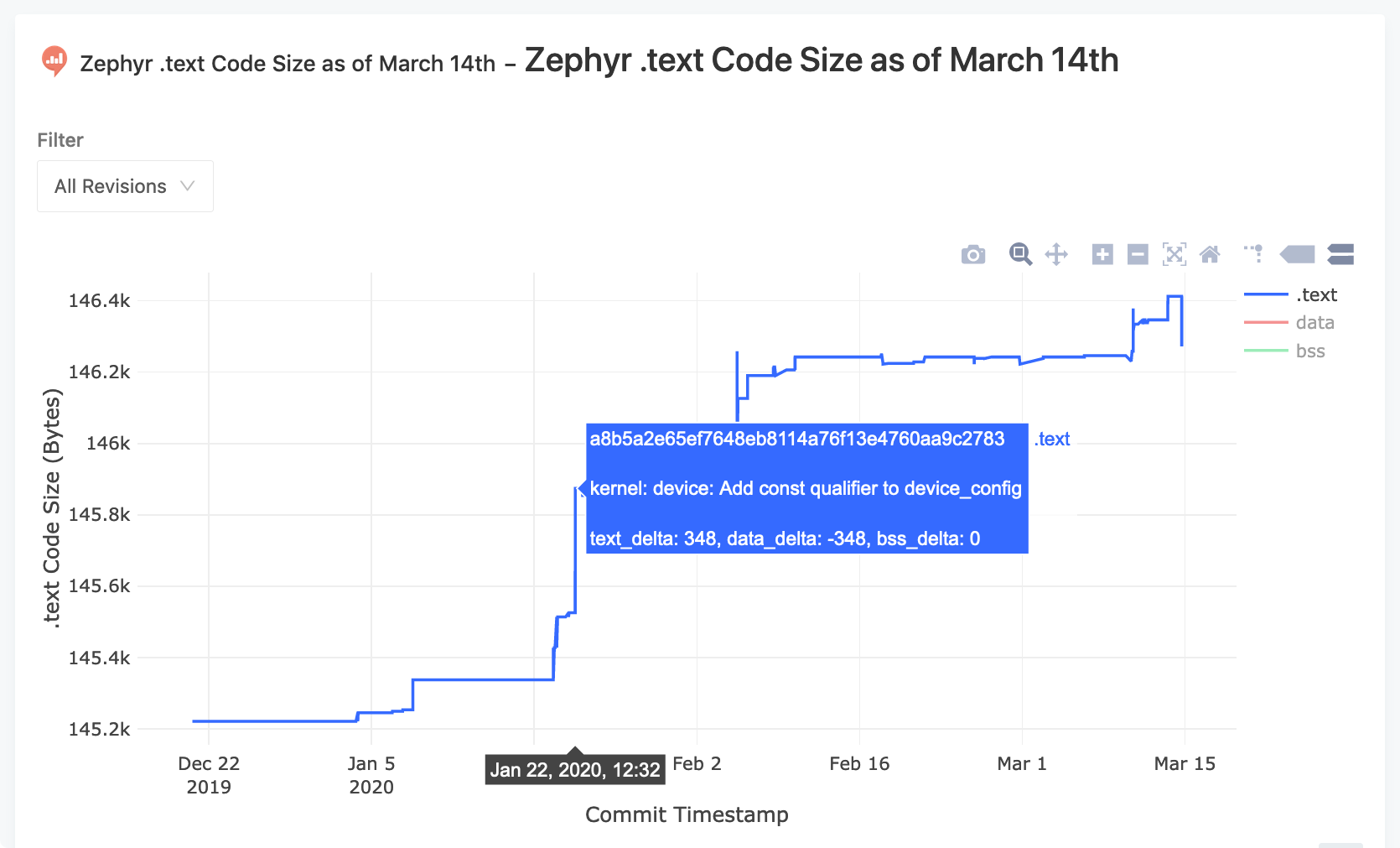

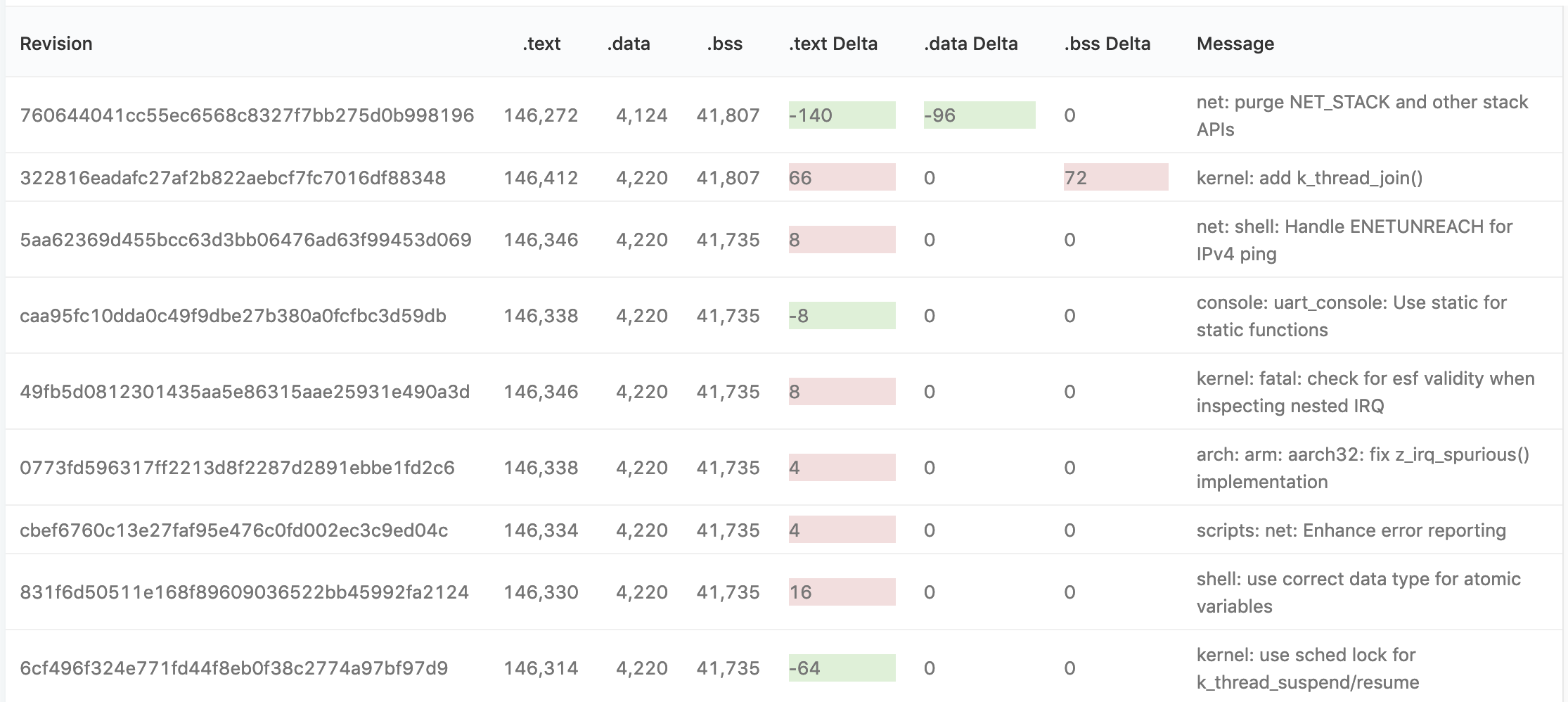

Here is a chart of the code size of the .text region for the last 2,500

commits:

and here is a way to show the extent of each commit’s impact on the overall code size:

If you want to see this data live, check out the Redash instance on Heroku!

Having these visualizations allow developers to dive into why code space has disappeared in the past and see where the code size is trending. If you ever need to find 500 bytes of code space and you have already taken the approaches listed in the GCC flags post, this is a good place to start.

Keeping the Code Size to a Minimum

Up until now, the code sizes we’ve analyzed had all already been committed to master. If our firmware is out of space today, we’d have to retro-actively refactor or revert these changes, both of which are difficult and time-consuming.

However, if you haven’t run out of space yet, or you are looking to keep the future code space bloat to a minimum, you need to ensure that every new commit and its code size impact is validated.

The best way I’ve found to keep code size in check is to calculate how much each pull-request contributes (or removes!) from the total. Now that we have most of the data we need, this is possible!

Code Size Deltas on Pull Requests

To get deltas on pull requests, we’ll need CI to run a script whenever one is

published or updated. This script will take the built binary, compute its code

size, and compare it against a given revision or the

git-merge-base5 of the “master” branch. git-merge-base takes

both revisions given and finds the most recent common ancestor between the two.

In the case of the Zephyr Project, this is the common ancestor between the base

of a pull-request and the origin/master branch.

In our

example code,

we have a command, diff which will do exactly this.

@cli.command()

@click.argument("binary")

@click.option("--build", default="default")

@click.option("--revision")

def diff(binary, build, revision):

"""

Calculate the size of the BINARY given, and compare it

to either the REVISION provided or the "merge-base" of the

current branch and master for the given BUILD.

"""

text, data, bss = _calculate_codesize(binary)

if not revision:

click.echo("Using `git merge-base` against master branch")

# git merge-base HEAD master

revision = _get_merge_base("HEAD", "master")

codesize = _fetch_codesize(build, revision)

if not codesize:

click.echo("No code size for build: {}, revision: {}".format(

build, revision))

return

text_delta = text - codesize.text

data_delta = data - codesize.data

bss_delta = bss - codesize.bss

click.echo("Comparing current binary against: {}".format(revision))

click.echo(dict(text=text_delta, data=data_delta, bss=bss_delta))

Let’s try it out! I went digging into the Zephyr Github Pull Requests page for a large changeset, and found a good candidate: Timeout API rework #23382.

We’ll check out the branch and build the firmware first.

# Check out the branch for #23382

$ cd zephyrproject/zephyr

$ git remote add pr git@github.com:andyross/zephyr.git

$ git fetch pr

$ git checkout pr/timeout-take-2

# Build the firmware

$ west build -b cc3220sf_launchxl samples/net/lwm2m_client --pristine

Next, let’s sanity check and ensure that the pull-request is based against a commit in the last 2,500, which would mean we had uploaded the size.

$ git merge-base master HEAD

7c5db4b755f73ab5f93a6456abaa5b97bd6aff7a

$ python ~/codesizes.py fetch 7c5db4b755f73ab5f93a6456abaa5b97bd6aff7a --build lwm2m_client

{'text': 146334, 'data': 4220, 'bss': 41735}

Perfect! We have the commit’s code size in our database. Let’s get the delta.

$ python ~/codesizes.py diff build/zephyr/zephyr.elf --build lwm2m_client

Using `git merge-base` against master branch

Comparing code size of current .elf against: 7c5db4b755f73ab5f93a6456abaa5b97bd6aff7a

+---------+--------+-------+-------+

| Region | .text | .data | .bss |

+---------+--------+-------+-------+

| Local | 146582 | 4220 | 41735 |

| Against | 146334 | 4220 | 41735 |

| Delta | 248 | 0 | 0 |

+---------+--------+-------+-------+

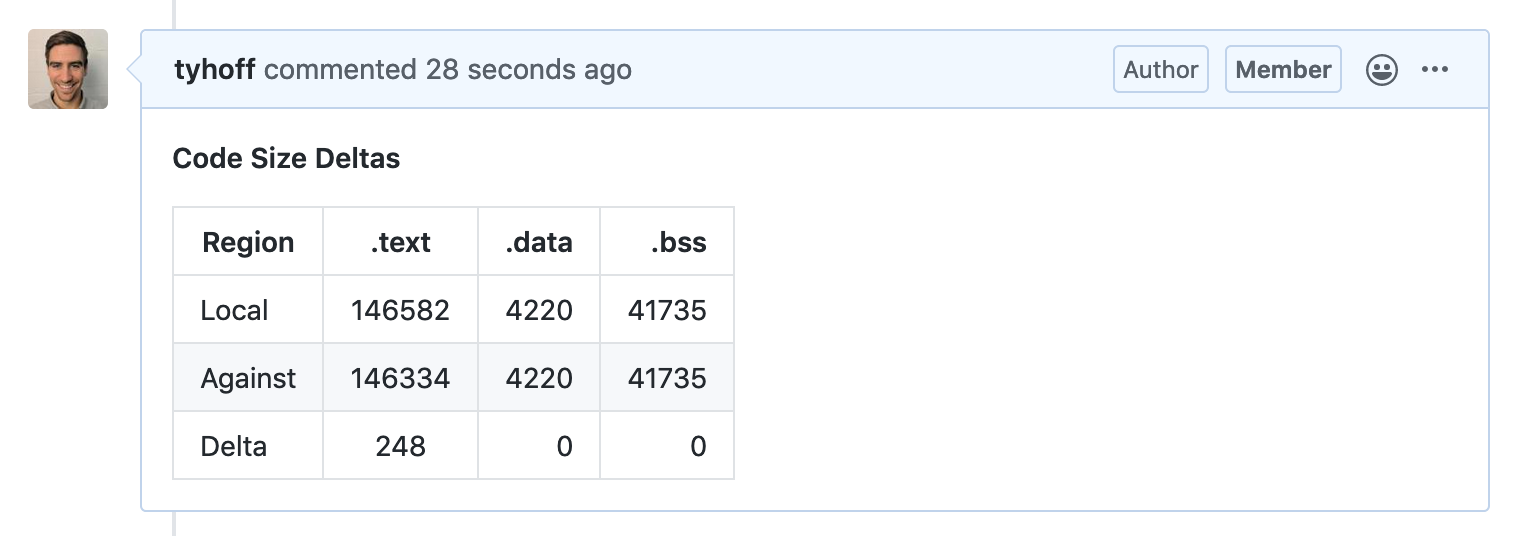

It turns out this pull-request adds roughly 250B to the master branch for our example firmware build! With this information in hand, the maintainers of the Zephyr Project can then decide whether the change is worth the bump in the firmware size. (I’d ✅)

The Last Mile

This is the end of the tutorial, but I wanted to share with you what I found works best at the previous companies I’ve worked for.

- Using Github Actions or the Github API, post a comment on each pull request.

Something like:

- Automatically add a firmware lead if the code size delta crosses a set threshold.

- Start tracking now. When you run out, it’s too late to make changes quickly.

Closing

I hope this post gave you the knowledge, tools, and inspiration to inspect your historical code size usage and be more proactive as your projects move forward. Show-stopping code space outages don’t have to be a surprise.

For those trying to investigate into their own code space usage further, here are a list of the resources I would start with:

- Code Size Optimization: GCC Compiler Flags

- Tools for Firmware Code Size Optimization

- Google Bloaty

- Puncover

All the code used in this blog post is available on Github.

See anything you'd like to change? Submit a pull request or open an issue on our GitHub